Asojano: AIDS, Poverty, and

Divine Retribution

Asojano: AIDS, Poverty, and

Divine Retribution

Asojano: AIDS, Poverty, and

Divine Retribution

Asojano: AIDS, Poverty, and

Divine Retribution

by Shloma Rosenberg

note: Asojano is the traditional name for the Orisha who is more commonly called Babaluaiye, Obaluaiye, or Omolu.

"Some places he festers in the pustules of skin diseases, rasps in the chest, distends in the rotten bowels of his victims. Other moments he is sleek, the spotted leopard, owner of earth before man began to claim it, prior to all kings, all chiefs. He is that destruction which insinuates itself into all activity, without which nothing important would ever be achieved. Father, they call him, for he is very old, outlawed again and again. How ridiculous to outlaw Him! The peregun flourishes. The leopard paints himself black and stalks under a borrowed name. No stranger can hear true tales of him. Awful to behold he is, a prowler, a hidden name."

--from Orisha: Gods of Yorubaland by Judith Gleason (Atheneum)

Whether it be in Africa, Cuba, Brazil, or the United States, the tales of Asojano invariably speak of his role as the Divine Outcast. Shunned for his plague-ravaged appearance, for fear of his contagion, or in hopes of avoiding his terrible wrath, Asojano is the Orisha who fills his worshipers with terrified awe and fearful respect.

In the New World, and particularly in the Lukumi tradition, Asojano's image has softened. This has been due in no small part to his association with Saint Lazarus. This Lazarus is the gentle and humble leper spoken of by Jesus in his lessons on humility, not Mary's dead and reborn brother. Through Saint Lazarus, or San Lázaro, Asojano has shed some of his more terrible aspects and become the mild-mannered patron of the poor, infirm, and sick. Despite this Catholic veneer, however, Oloshas still retain the image of Asojano as an awesome and formidable divinity with a tenuous hold on his destructive powers.

Asojano is described as the Orisha of plagues and epidemics. He is often referred to as the messenger of the wrath of God. In this capacity, he has the power to deliver unto the world the terrible results of its actions as well as the power to lift those same burdens from the shoulders of his victims.

To fully understand the nature of this Orisha, one must first examine the pataki in which his tale is related. Regardless of which story you hear or from which country it comes, Asojano is repeatedly described as a leper, a beggar, and an outcast. It is said that wherever he went, people would throw buckets of water in his wake to clear away the osogbo that followed him. He represents every element of society with which the dominant culture does not wish to deal. In days gone by, Asojano was the patron of plague victims, beggars, and all social castoffs, who were said to be his representatives on earth. Today he has become the patron of those afflicted with HIV and AIDS.

To view those who suffer from epidemics and poverty as the "victims" of the work of Asojano is a gross misunderstanding of this Orisha's nature. When we look to the pataki, we see that it is not Asojano, the plague victim, the mendicant, who is viewed as the antagonist, rather, it is the society at large and, more often, its ruler. Asojano is portrayed as a humble man doing his best to make his way despite his infirmities. He is mocked, scorned, and sent into exile. Only then does his true power become apparent. The endings of these stories invariably find the cruel ruler or the mocking villagers falling victim to the very plagues for which they persecuted Asojano.

I find this to be a brilliant and prophetic analysis of the nature of society and culture as well as of the havoc wreaked upon the earth and its inhabitants BY its inhabitants, led by the dominant social group. When we see that the victims of plagues and poverty are rarely members of the ruling class (at first, anyway), we can begin to understand the parallels of our modern culture to the pataki of Asojano. When we look further and see what happens when plagues and poverty begin to affect the upper rungs of the socioeconomic ladder, things become even clearer.

The history of the AIDS epidemic reads like a modern retelling of the story of Asojano. When the plague first hit, its victims were primarily gay men, Haitians, and intravenous drug users. The government did want nothing to recognize the fact that a problem even existed, let alone do anything about it. It is now a well-known fact that Ronald Reagan never mentioned AIDS in public during his second term in office. In the first 12 months after the epidemic was officially recognized, less than one million dollars of government funds were allocated to the research necessary to find a cure, as compared to 12 million dollars spent on finding a cure for Legionnaires' disease in the first 30 DAYS after the recognition of that epidemic (which hit a comparatively small number of people--mostly white, upper-middle- to upper-class men).

At that time, stand-up comedy routines (remember Sam Kinison?), bumper stickers ("No AIDS" with a red slash through a silhouette of a man bent over), and a host of other pop culture phenomena mocked those afflicted with AIDS. Hospitals turned away those infected with the virus; men who were known or suspected to be gay lost their jobs; assaults and other hate crimes perpetrated on gay men hit an all-time high. It was not until the epidemic spread to the heterosexual community, to nurses who were accidentally pricked with needles, to children born of HIV-infected mothers--in short, to the general population--that a move was made toward finding an end to this plague. Even now discrimination continues, with the "undesirables" falling dead as the world rallies around "safe" poster children: the young, the straight, the famous, the white.

As with AIDS, no one wants to do anything about poverty until it begins to creep up their back steps. Those in power are happy to have the inner cities, impoverished backwater towns, and Third World countries on which to blame the world's problems. The beggar on the street, the woman at the freeway ramp with her cardboard plea, and the sheet-metal shacks on the outskirts of town are reassuring reminders that there are those who have and those who have not, that nothing that none of the world's problems are the fault of the businessman or the politician, that there will be plenty left for the big guys. The social elite, in part, create these situations of want and need by their own conspicuous consumption as well as by the erasure of the working class by commodity fetishism. It is only when the situation inevitably begins to bite into the fatter of the world's wallets that anyone mentions anything about tightening belts. As with AIDS, the solutions offered are token. Make a couple of insignificant spending cuts (usually on those programs that might actually help to eradicate some of the problem), scare up a few "I Pulled Myself Up by My Bootstraps" poster children for the lecture circuit, and legislate more firmly the boundaries of the wasteland of the impoverished. The point is deliberately missed.

At the end of many of the versions of the pataki of Asojano's banishment, we often see those who scorned him making ebo of appeasement. In many versions it is too late. Asojano neither forgives nor is fooled easily. As we see in the sacred stories and in the world around us, those who view themselves as separate from the poor and immune to the world's epidemics invariably discover their sameness with the passage of time. Even with these parallels, we must still examine the concept of divine retribution. Are those who suffer in the poverty and disease manifested by Asojano suffering as a result of their own actions? Often they are. Yet it is still not quite that easy. Although to some extent we create our own reality (after all, we did choose our Ori, and we do have the power to alter our course and be properly aligned with our fullest potential), no one person exists in a vacuum. We are still subject to the larger, communally created reality.

It is true that AIDS spread quickly among gay men because of a tendency toward promiscuity in the bar and bathhouse culture in which many gay men move. It is also true that this segment of gay culture is to a large extent the creation of the dominant culture that suppresses the possibility of committed and monogamous gay relationships. The societal hatred directed toward gays is often accepted and internalized by gays themselves, manifesting itself in promiscuity and other self-destructive tendencies. In this way, self-created reality works hand-in-hand with the reality created by the larger body. One thing that the larger body forgot as it sat on its hands in the early days of the epidemic is that self-hate, self-destruction, and promiscuity are proportionately identical for other reasons in the heterosexual world. In addition to the part played by those who contracted the disease, the government's indifference to their plight left the public uneducated, unprotected, and fearful and to a great degree still does. This contributed to the spread of the plague in a far more damaging way than the actions of any individual or social group.

Poverty has worked the same way. In Third World countries, resources are drained by those in power, leaving the citizens with few or no tools with which to move from the position of need in which they find themselves. In the inner cities, internalized self-hate and an overwhelming despair among various ethnic groups not only leads to self-destructive lifestyles but also engenders warfare between these groups, born in a large part from the need for a tangible and accessible enemy. This, coupled with factions of government and corporate society that have a vested interest in maintaining poverty levels and internal conflict, leaves the impoverished with few options but to remain so.

If we are to learn anything from the pataki of Asojano, it is that he cannot be banished. Those afflicted with disease, poverty, and famine are not his victims; they are his messengers. To attempt to relegate them to an invisible position has never worked. Reality is not created on a level individual enough for Olorun to direct a plague at a certain segment of society. Those who are ill or impoverished are not victims of their own karma. They are the warning signs, the harbingers of the wrath of God that is yet to come. They are the signposts that tell us that we cannot do unto others without simultaneously doing unto ourselves. We cannot point at those affected by poverty and disease without pointing at ourselves.

If we understand that we, the people of this world, are cells in one body, then we must realize that together we create our situation. Whether we are the impoverished citizen of the inner city or the wealthy inhabitant of the ivory tower, whether we are the AIDS-stricken prostitute or the fundamentalist congressman, we must understand that the desire to place blame only serves to blind us to our own responsibility.

To view each person as an island is to dismember the body of God. It is more comfortable in the short term to think that tragedies only befall "those people," but as in the tales of the casting out of Asojano, we will eventually discover that we are "those people." Until we understand that we are the impoverished, we are the plague victims, we are the outcasts, Asojano will continue to turn on us as we mock him.

This article would not have been the same if it had it not been for my

friendship with the brilliant Adrienne Young of the University of Michigan,

whose insight into the nature of power and power relationships in society is

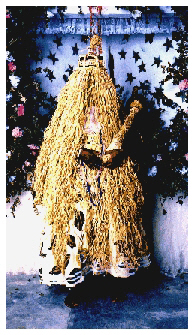

unparalleled. Modupe O. Photo from

"Divine Inspiration" by Phyllis Galembo (U of NM Press)